GPU computing with Chapel

June 12th

1:30pm-4:30pm Pacific Time

Chapel was designed as a parallel-first programming language targeting any hardware that supports parallel execution: multicore processors, multiple nodes in an HPC cluster, and now also GPUs on HPC systems. This is very different from the traditional approach to parallel programming in which you would use a dedicated tool for each level of hardware parallelism, e.g. MPI, or OpenMP, or CUDA, etc.

Later in this workshop I will show a compact Chapel code that uses multiple nodes on a cluster, multiple GPUs on each node, and automatically utilizes all available (in our Slum job) CPU cores on each node, while copying the data as needed between all these hardware layers. But let’s start with the basics!

Running GPU Chapel on the Alliance systems

In general, you need to configure and compile Chapel for your specific GPU type and your specific cluster

interconnect. For NVIDIA and AMD GPUs (the only ones currently supported), you must use LLVM as the backend

compiler. With NVIDIA GPUs, you must build LLVM to use LLVM’s NVPTX

backend to support GPU programming, so usually you cannot use the

system-provided LLVM module – instead you should set CHPL_LLVM=bundled during Chapel compilation.

As of this writing, on the Alliance systems, you can use GPUs from Chapel on the following systems:

- native multi-locale on Cedar, Graham, Béluga, Narval; the binaries might not be in place everywhere, so please get in touch if you want to run it on a specific system

- on an Arbutus VM in a project with access to vGPUs (our plan for today)

- via a single-locale GPU Chapel container on any Alliance system (clusters, cloud) with NVIDIA GPUs; let me know if you would like to access this container

Efforts are underway to compile native Chapel 2.2 as a series of modules on all Alliance systems, but that might take a while.

Running GPU Chapel on your computer

If you have an NVIDIA GPU on your computer and run Linux, and have all the right GPU drivers and CUDA installed, it should be fairly straightforward to compile Chapel with GPU support. Here is what worked for me in AlmaLinux 9.4. Please let me know if these steps do not work for you.

In Windows, Chapel with GPU support works under the Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) as explained in this post. You could also run Chapel inside a Docker container, although you need to find a GPU-enabled Docker image.

Today’s setup

Today’s we’ll run Chapel on the virtual training cluster. We’ll now distribute the usernames and passwords – let’s try to log in.

There are two Chapel configurations we will use today.

- Chapel with GPU support compiled for NVIDIA cards. We have 1 virtual GPU on the training cluster to share among all participants and the instructor, so we won’t be able to use it all at the same time. The idea is to try your final production code on this GPU allocating it only for a couple of minutes at a time per user:

#!/bin/bash

#SBATCH --time=00:02:00

#SBATCH --mem=3600

#SBATCH --gpus-per-node=1

nvidia-smi

chpl --fast test.chpl

./test

source /project/def-sponsor00/shared/syncHPC/startSingleLocaleGPU.sh

sbatch submit.sh

- We will be doing most debugging on CPUs using the so-called ‘CPU-as-device’ mode to run a GPU code on a

CPU. This is very handy for debugging a Chapel GPU code on a computer without a dedicated GPU and/or vendor

SDK installed. You can find more details on this mode

here. To enable this mode, I

recompiled Chapel with

export CHPL_GPU=cpu, but you need to load this version of Chapel separately, and you can use it via an interactive job:

source /project/def-sponsor00/shared/syncHPC/startSingleLocaleCPUasDevice.sh

salloc --time=2:0:0 --mem=3600

chpl --fast test.chpl

./test

In this mode there are some restrictions, e.g. data movement between the device and the host will not be

captured (as there are no data moved!), some parallel reductions might not be available in this mode (to be

confirmed), and the GPU kernel breakdown might be different. Still, all GPU kernels will be launched on the

CPU, and you can even use some of the Chapel’s diagnostic features in this mode, e.g. @assertOnGpu and

@gpu.assertEligible attributes will fail at compile time for ineligible loops.

Useful built-in variables

From inside your Chapel code, you can access the following predefined variables:

Localesis the list of locales (nodes) that your code can run on (invoked in code execution)numLocalesis the number of these localeshereis the current locale (node), and by extension current CPUhere.nameis its namehere.maxTaskParis the number of CPU cores on this localehere.gpusis the list of available GPUs on this locale (sometimes called “sublocales”)here.gpus.sizeis the number of available GPUs on this localehere.gpus[0]is the first GPU on this locale

Let’s try some of these out; store this code as test.chpl:

writeln("Locales: ", Locales);

writeln("on ", here.name, " I see ", here.gpus.size, " GPUs");

writeln("and their names are: ", here.gpus);

chpl --fast test.chpl

./test

Locales: LOCALE0

on cdr2514.int.cedar.computecanada.ca I see 1 GPUs

and their names are: LOCALE0-GPU0

There is one GPU (even in ‘CPU-as-device’ mode), and it is available to us as the first (and only) element of

the array here.gpus.

Our first GPU code

To benefit from GPU acceleration, you want to run a computation that can be broken into many independent identical pieces. An obvious example is a for loop in which each loop iteration does not depend on other iterations. Let’s run such an example on the GPU:

config const n = 10;

on here.gpus[0] {

var A: [1..n] int; // kernel launch to initialize an array

foreach i in 1..n do // thread parallelism on a CPU or a GPU => kernel launch

A[i] = i**2;

writeln("A = ", A); // copy A to host

}

A = 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100

- the array

Ais stored on the GPU - order-independent loops will be executed in parallel on the GPU

- if instead of parallel

foreachwe use serialfor, the loop will run on the CPU - in our case the array

Ais both stored and computed on the GPU in parallel - currently, to be computed on a GPU, an array must be stored on that GPU

- in general, when you run a code block on the device, parallel lines inside will launch kernels

Alternative syntax

We can modify this code so that it runs on a GPU if present; otherwise, it will run on the CPU:

var operateOn =

if here.gpus.size > 0 then here.gpus[0] // use the first GPU

else here; // use the CPU

writeln("operateOn: ", operateOn);

config const n = 10;

on operateOn {

var A: [1..n] int;

foreach i in 1..n do

A[i] = i**2;

writeln("A = ", A);

}

Of course, in ‘CPU-as-device’ mode this code will always run on the CPU.

You can also force a GPU check by hand:

if here.gpus.size == 0 {

writeln("need a GPU ...");

exit(1);

}

operateOn = here.gpus[0];

GPU diagnostics

Wrap our code into the following lines:

use GpuDiagnostics;

startGpuDiagnostics();

...

stopGpuDiagnostics();

writeln(getGpuDiagnostics());

operateOn: LOCALE0-GPU0

A = 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100

(kernel_launch = 2, host_to_device = 0, device_to_host = 10, device_to_device = 0)

in 'CPU-as-device' mode: (kernel_launch = 2, host_to_device = 0, device_to_host = 0, device_to_device = 0)

Let’s break down the events:

- we have two kernel launches

var A: [1..n] int; // kernel launch to initialize an array

foreach i in 1..n do // kernel launch to run a loop in parallel

A[i] = i**2;

- we copy 10 array elements device-to-host to print them (not shown in ‘CPU-as-device’ mode)

writeln("A = ", A);

- no other data transfer

Let’s take a look at the example from https://chapel-lang.org/blog/posts/intro-to-gpus. They define a function:

use GpuDiagnostics;

proc numKernelLaunches() {

stopGpuDiagnostics(); // assuming you were running one before

var result = getGpuDiagnostics().kernel_launch;

resetGpuDiagnostics();

startGpuDiagnostics(); // restart diagnostics

return result;

}

which can then be applied to these 3 examples (all in one on here.gpus[0] block):

startGpuDiagnostics();

on here.gpus[0] {

var E = 2 * [1,2,3,4,5]; // one kernel launch to initialize the array

writeln(E);

assert(numKernelLaunches() == 1);

use Math;

const n = 10;

var A = [i in 0..#n] sin(2 * pi * i / n); // one kernel launch

writeln(A);

assert(numKernelLaunches() == 1);

var rows, cols = 1..5;

var Square: [rows, cols] int; // one kernel launch

foreach (r, c) in Square.indices do // one kernel launch

Square[r, c] = r * 10 + c;

writeln(Square);

assert(numKernelLaunches() == 2); // 2 on GPU and 7 on CPU-as-device

}

Question 1

Let’s play with this in the CPU-as-device mode! Make the upper limit ofrows, cols a config variable,

recompile, and play with the array size.

Verifying if a loop can run on a GPU

The loop attribute @assertOnGpu (applied to a loop) does two things:

- at compilation, will fail to compile a code that cannot run on a GPU and will tell you why

- at runtime, will halt execution if called from outside a GPU

Consider the following serial code:

config const n = 10;

on here.gpus[0] {

var A: [1..n] int;

for i in 1..n do

A[i] = i**2;

writeln("A = ", A);

}

A = 1 4 9 16 25 36 49 64 81 100

This code compiles fine (chpl --fast test.chpl), and it appears to run fine, printing the array. But it

does not run on the GPU! Let’s mark the for loop with @assertOnGpu and try to compile it again. Now we

get:

error: loop marked with @assertOnGpu, but 'for' loops don't support GPU execution

Serial for loops cannot run on a GPU! Without @assertOnGpu the code compiled for and ran on the CPU. To

port this code to the GPU, replace for with either foreach or forall (both are parallel loops), and it

should compile with @assertOnGpu.

Alternatively, you can count kernel launches – it’ll be zero for the for loop.

More on @assertOnGpu and other attributes at https://chapel-lang.org/docs/main/modules/standard/GPU.html.

Timing on the CPU

Let’s pack our computation into a function, so that we can call it from both a CPU and a GPU. For timing, we

can use a stopwatch from the Time module:

use Time;

config const n = 10;

var watch: stopwatch;

proc squares(device) {

on device {

var A: [1..n] int;

foreach i in 1..n do

A[i] = i**2;

writeln("A = ", A[n-2..n]); // last 3 elements

}

}

writeln("--- on CPU:"); watch.start();

squares(here);

watch.stop(); writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

watch.clear();

writeln("--- on GPU:"); watch.start();

squares(here.gpus[0]);

watch.stop(); writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

$ chpl --fast test.chpl

$ ./test --n=100_000_000

--- on CPU:

A = 9999999600000004 9999999800000001 10000000000000000

It took 7.94598 seconds

--- on GPU:

A = 9999999600000004 9999999800000001 10000000000000000

It took 0.003673 seconds

You can also call start and stop functions from inside the on device block – they will still run on the

CPU. We will see an example of this later in this workshop.

Timing on the GPU

Obtaining timing from within a running CUDA kernel is tricky as you are running potentially thousands of

simultaneous threads, so you definitely cannot measure the wallclock time. However, you can measure GPU clock

cycles spent on a partucular part of the kernel function. The GPU module provides a function gpuClock()

that returns the clock cycle counter (per multiprocessor), and it needs to be called to time code blocks

within a GPU-enabled loop.

Here is an example (modelled after

measureGpuCycles.chpl)

to demonstrate its use. This is not the most efficient code, as on the GPU we are parallelizing the loop with

n=10 iterations, and then inside each iteration we run a serial loop to keep the (few non-idle) GPU cores

busy, but it gives you an idea.

use GPU;

config const n = 10;

on here.gpus[0] {

var A: [1..n] int;

var clockDiff: [1..n] uint;

@assertOnGpu foreach i in 1..n {

var start, stop: uint;

A[i] = i**2;

start = gpuClock();

for j in 0..<1000 do

A[i] += i*j;

stop = gpuClock();

clockDiff[i] = stop - start;

}

writeln("Cycle count = ", clockDiff);

writeln("Time = ", (clockDiff[1]: real) / (gpuClocksPerSec(0): real), " seconds");

writeln("A = ", A);

}

Cycle count = 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132 227132

Time = 0.148452 seconds

A = 49501 49604 49709 49816 49925 50036 50149 50264 50381 50500

Prime factorization of each element of a large array

Now let’s compute a more interesting problem where we do some significant processing of each element, but independently of other elements – this will port nicely to a GPU.

Prime factorization of an integer number is finding all its prime factors. For example, the prime factors of 60 are 2, 2, 3, and 5. Let’s write a function that takes an integer number and returns the sum of all its prime factors. For example, for 60 it will return 2+2+3+5 = 12, for 91 it will return 7+13 = 20, for 101 it will return 101, and so on.

proc primeFactorizationSum(n: int) {

var num = n, output = 0, count = 0;

while num % 2 == 0 {

num /= 2;

count += 1;

}

for j in 1..count do output += 2;

for i in 3..(sqrt(n:real)):int by 2 {

count = 0;

while num % i == 0 {

num /= i;

count += 1;

}

for j in 1..count do output += i;

}

if num > 2 then output += num;

return output;

}

We can test it quickly:

writeln(primeFactorizationSum(60));

writeln(primeFactorizationSum(91));

writeln(primeFactorizationSum(101));

writeln(primeFactorizationSum(100_000_000));

Since 1 has no prime factors, we will start computing from 2, and then will apply this function to all

integers in the range 2..n, where n is a larger number. We will do all computations separately from

scratch for each number, i.e. we will not cache our results (caching can significantly speed up our

calculations but the point here is to focus on brute-force computing).

With the procedure primeFactorizationSum defined, here is the CPU version primesSerial.chpl:

config const n = 10;

var A: [2..n] int;

for i in 2..n do

A[i] = primeFactorizationSum(i);

var lastFewDigits =

if n > 5 then n-4..n // last 5 digits

else 2..n; // or fewer

writeln("A = ", A[lastFewDigits]);

Here is the GPU version primesGPU.chpl:

config const n = 10;

on here.gpus[0] {

var A: [2..n] int;

@gpu.assertEligible foreach i in 2..n do

A[i] = primeFactorizationSum(i);

var lastFewDigits =

if n > 5 then n-4..n // last 5 digits

else 2..n; // or fewer

writeln("A = ", A[lastFewDigits]);

}

chpl --fast primesSerial.chpl

./primesSerial --n=10_000_000

chpl --fast primesGPU.chpl

./primesGPU --n=10_000_000

In both cases we should see the same output:

A = 4561 1428578 5000001 4894 49

Let’s add timing to both codes:

use Time;

var watch: stopwatch;

...

watch.start();

...

watch.stop(); writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

Note that this problem does not scale linearly with n, as with larger numbers you will get more primes. Here

are my timings on Cedar’s V100 GPU:

| n | CPU time in sec | GPU time in sec | speedup factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1_000_000 | 3.04051 | 0.001649 | 1844 |

| 10_000_000 | 92.8213 | 0.042215 | 2199 |

| 100_000_000 | 2857.04 | 1.13168 | 2525 |

Finer control

There are various settings that you can fine-tune via attributes for maximum performance, e.g. you can change the number of threads per block (default 512, should be a multiple of 32) when launching kernels:

@gpu.blockSize(64) foreach i in 1..128 { ...}

You can also change the default when compiling Chapel via CHPL_GPU_BLOCK_SIZE variable, or when compiling

Chapel codes by passing the flag --gpu-block-size=<block_size> to Chapel compiler

Another setting to play with is the number of iterations per thread:

@gpu.itersPerThread(4) foreach i in 1..128 { ... }

This setting is probably specific to your computational problem. For these and other per-kernel attributes, please see this page.

Multiple locales and multiple GPUs

If we have access to multiple locales and then multiple GPUs on each of those locales, we would utilize all this processing power through two nested loops, first cycling through all locales and then through all available GPUs on each locale:

coforall loc in Locales do

on loc {

writeln("on ", loc.name, " I see ", loc.gpus.size, " GPUs");

coforall gpu in loc.gpus {

on gpu {

... do some work in parallel ...

}

}

}

Here we assume that we are running inside a multi-node job on the cluster, e.g.

salloc --time=1:0:0 --nodes=3 --mem-per-cpu=3600 --gpus-per-node=2 --account=...

chpl --fast test.chpl

./test -nl 3

How would we use this approach in practice? Let’s consider our primes factorization problem. Suppose we want

to collect the results on one node (LOCALE0), maybe for printing or for some additional processing. We need to

break our array A into pieces, each computed on a separate GPU from the total pool of 6 GPUs available to us

inside this job. Here is our approach, following the ideas outlined in

https://chapel-lang.org/blog/posts/gpu-data-movement – let’s store this file as primesGPU-distributed.chpl:

import RangeChunk.chunks;

proc primeFactorizationSum(n: int) {

...

}

config const n = 1000;

var A_on_host: [2..n] int; // suppose we want to collect the results on one node (LOCALE0)

// let's assume that numLocales = 3

coforall (loc, locChunk) in zip(Locales, chunks(2..n, numLocales)) {

/* loc=LOCALE0, locChunk=2..334 */

/* loc=LOCALE1, locChunk=335..667 */

/* loc=LOCALE2, locChunk=668..1000 */

on loc {

writeln("loc = ", loc, " chunk = ", locChunk);

const numGpus = here.gpus.size;

coforall (gpu, gpuChunk) in zip(here.gpus, chunks(locChunk, numGpus)) {

/* on LOCALE0 will see gpu=LOCALE0-GPU0, gpuChunk=2..168 */

/* gpu=LOCALE0-GPU1, gpuChunk=169..334 */

on gpu {

writeln("loc = ", loc, " gpu = ", gpu, " chunk = ", gpuChunk);

var A_on_device: [gpuChunk] int;

foreach i in gpuChunk do

A_on_device[i] = primeFactorizationSum(i);

A_on_host[gpuChunk] = A_on_device; // copy the chunk from the GPU via the host to LOCALE0

}

}

}

}

var lastFewDigits = if n > 5 then n-4..n else 2..n; // last 5 or fewer digits

writeln("last few A elements: ", A_on_host[lastFewDigits]);

Running multi-GPU code on Cedar

When we run this code on 2 Cedar nodes with 2 GPUs per node:

source /home/razoumov/startMultiLocaleGPU.sh

cd ~/scratch

salloc --time=0:15:0 --nodes=2 --cpus-per-task=1 --mem-per-cpu=3600 --gpus-per-node=v100l:2 \

--account=cc-debug

chpl --fast primesGPU-distributed.chpl

./primesGPU-distributed -nl 2

we get the following output:

loc = LOCALE0 chunk = 2..501

loc = LOCALE0 gpu = LOCALE0-GPU0 chunk = 2..251

loc = LOCALE0 gpu = LOCALE0-GPU1 chunk = 252..501

loc = LOCALE1 chunk = 502..1000

loc = LOCALE1 gpu = LOCALE1-GPU0 chunk = 502..751

loc = LOCALE1 gpu = LOCALE1-GPU1 chunk = 752..1000

last few A elements: 90 997 501 46 21

Distributed A_on_host array

In the code above, the array A_on_host resides entirely in host’s memory on one node. With a sufficiently

large problem, you can distribute A_on_host across multiple nodes using block distribution:

use BlockDist; // use standard block distribution module to partition the domain into blocks

config const n = 1000;

const distributedMesh: domain(1) dmapped new blockDist(boundingBox={2..n}) = {2..n};

var A_on_host: [distributedMesh] int;

This way, when copying from device to host, you will copy only to the locally stored part of A_on_host.

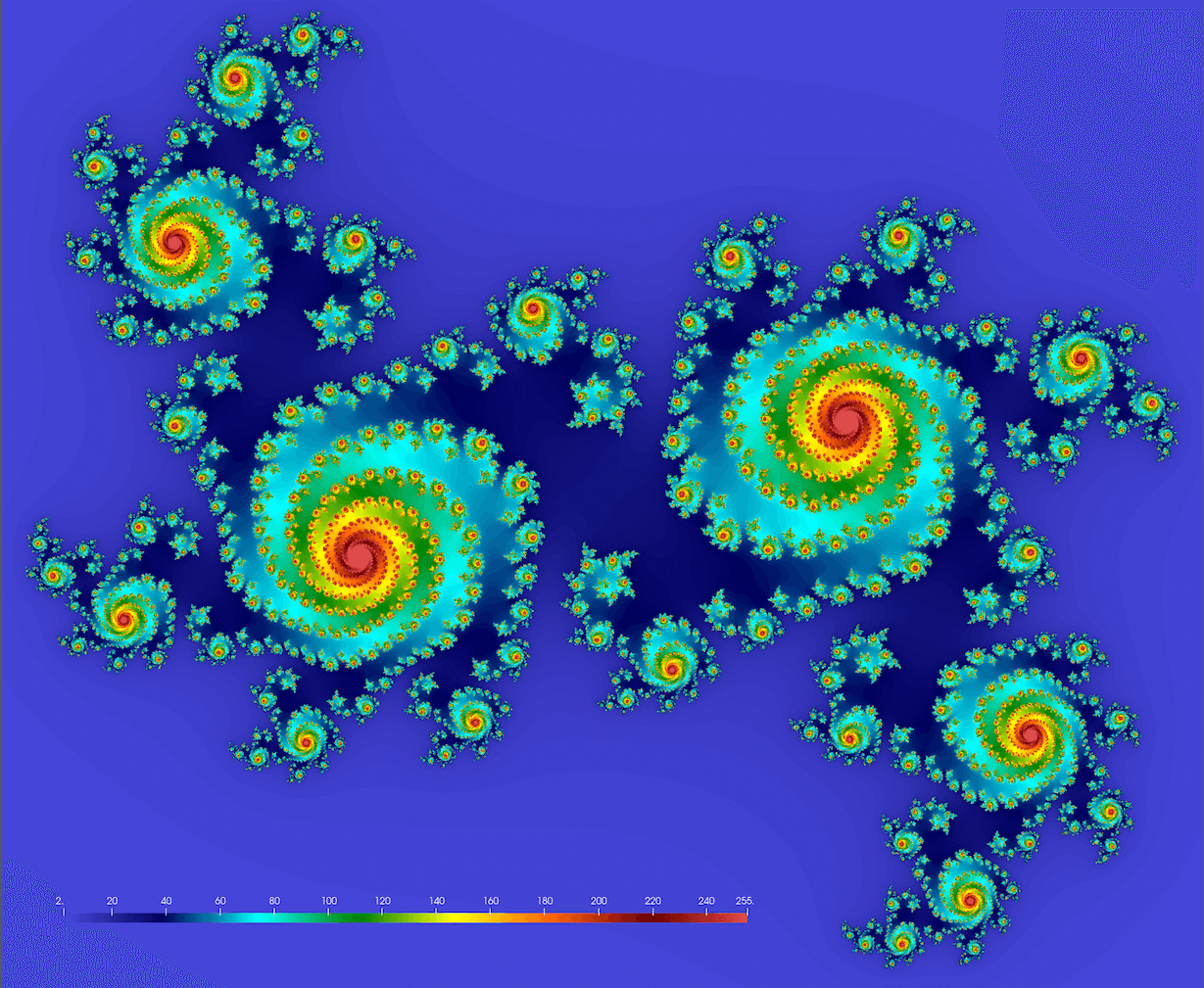

Julia set problem

In the Julia set problem we need to compute a set of points on the

complex plane that remain bound under infinite recursive transformation

- pick a point

- compute iterations

- store the iteration number

- limit max iterations at 255

4.1 if

4.2 the quicker a point diverges, the lower its - plot

We should get something conceptually similar to this figure (here

Note: you might want to try these values too:

Below is the serial code juliaSetSerial.chpl:

use Time;

config const n = 2_000; // 2000^2 image

var watch: stopwatch;

config const save = false;

proc pixel(z0) {

const c = 0.355 + 0.355i;

var z = z0*1.2; // zoom out

for i in 1..255 {

z = z*z + c;

if z.re**2+z.im**2 >= 16 then // abs(z)>=4 does not work with LLVM

return i;

}

return 255;

}

writeln("Computing ", n, "x", n, " Julia set ...");

watch.start();

var stability: [1..n,1..n] int;

for i in 1..n {

var y = 2*(i-0.5)/n - 1;

for j in 1..n {

var point = 2*(j-0.5)/n - 1 + y*1i;

stability[i,j] = pixel(point);

}

}

watch.stop();

writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

chpl --fast juliaSetSerial.chpl

./juliaSetSerial

It took me 2.34679 seconds to compute a

Porting the Julia set problem to a GPU

Let’s port this problem to a GPU! Copy juliaSetSerial.chpl to juliaSetGPU.chpl and make the following

changes.

Step 1 (optional, will work only on a physical GPU):

> if here.gpus.size == 0 {

> writeln("need a GPU ...");

> exit(1);

> }

As of this writing, Chapel 2.2 does not support complex arithmetic on a GPU. Independently of the precision,

you will get errors at compilation (if marked with @gpu.assertEligible):

error: Loop is marked with @gpu.assertEligible but is not eligible for execution on a GPU

... function calls out to extern function (_chpl_complex128), which is not marked as GPU eligible

... function calls out to extern function (_chpl_complex64), which is not marked as GPU eligible

If not marked with @gpu.assertEligible, the code compiles with complex arithmetic on a GPU, but it seems to

take forever to finish.

Fortunately, we can implement complex arithmetic manually:

Step 2:

< proc pixel(z0) {

---

> proc pixel(x0,y0) {

Step 3:

< var z = z0*1.2; // zoom out

---

> var x = x0*1.2; // zoom out

> var y = y0*1.2; // zoom out

Step 4:

< z = z*z + c;

---

> var xnew = x**2 - y**2 + c.re;

> var ynew = 2*x*y + c.im;

> x = xnew;

> y = ynew;

Step 5:

< if z.re**2+z.im**2 >= 16 then // abs(z)>=4 does not work with LLVM

---

> if x**2+y**2 >= 16 then

Step 6:

< var stability: [1..n,1..n] int;

---

> on here.gpus[0] {

> var stability: [1..n,1..n] int;

...

> }

Step 7:

< for i in 1..n {

---

> @gpu.assertEligible foreach i in 1..n {

Step 8:

< var point = 2*(j-0.5)/n - 1 + y*1i;

< stability[i,j] = pixel(point);

---

> var x = 2*(j-0.5)/n - 1;

> stability[i,j] = pixel(x,y);

Here is the full GPU version of the code juliaSetGPU.chpl:

use Time;

config const n = 2_000; // 2000^2 image

var watch: stopwatch;

config const save = false;

if here.gpus.size == 0 {

writeln("need a GPU ...");

exit(1);

}

proc pixel(x0,y0) {

const c = 0.355 + 0.355i;

var x = x0*1.2; // zoom out

var y = y0*1.2; // zoom out

for i in 1..255 {

var xnew = x**2 - y**2 + c.re;

var ynew = 2*x*y + c.im;

x = xnew;

y = ynew;

if x**2+y**2 >= 16 then

return i;

}

return 255;

}

writeln("Computing ", n, "x", n, " Julia set ...");

watch.start();

on here.gpus[0] {

var stability: [1..n,1..n] int;

@gpu.assertEligible foreach i in 1..n {

var y = 2*(i-0.5)/n - 1;

for j in 1..n {

var x = 2*(j-0.5)/n - 1;

stability[i,j] = pixel(x,y);

}

}

}

watch.stop();

writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

It took 0.017364 seconds on the GPU.

| Problem size | CPU time in sec | GPU time in sec | speedup factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.64477 | 0.017372 | 95 | |

| 6.5732 | 0.035302 | 186 | |

| 26.1678 | 0.067307 | 389 | |

| 104.212 | 0.131301 | 794 |

Adding plotting to run on a GPU

Chapel’s Image library lets you write arrays

of pixels to a PNG file. The following code – when added to the non-GPU code juliaSetSerial.chpl – writes

the array stability to a file 2000.png assuming you

- download the colour map in CSV and

- add the file

sciplot.chpl(pasted below)

writeln("Plotting ...");

use Image, Math, sciplot;

watch.clear();

watch.start();

const smin = min reduce(stability);

const smax = max reduce(stability);

var colour: [1..n, 1..n] 3*int;

var cmap = readColourmap('nipy_spectral.csv'); // cmap.domain is {1..256, 1..3}

for i in 1..n {

for j in 1..n {

var idx = ((stability[i,j]:real-smin)/(smax-smin)*255):int + 1; //scale to 1..256

colour[i,j] = ((cmap[idx,1]*255):int, (cmap[idx,2]*255):int, (cmap[idx,3]*255):int);

}

}

var pixels = colorToPixel(colour); // array of pixels

writeImage(n:string+".png", imageType.png, pixels);

watch.stop();

writeln('It took ', watch.elapsed(), ' seconds');

// save this as sciplot.chpl

use IO;

use List;

proc readColourmap(filename: string) {

var reader = open(filename, ioMode.r).reader();

var line: string;

if (!reader.readLine(line)) then // skip the header

halt("ERROR: file appears to be empty");

var dataRows : list(string); // a list of lines from the file

while (reader.readLine(line)) do // read all lines into the list

dataRows.pushBack(line);

var cmap: [1..dataRows.size, 1..3] real;

for (i, row) in zip(1..dataRows.size, dataRows) {

var c1 = row.find(','):int; // position of the 1st comma in the line

var c2 = row.rfind(','):int; // position of the 2nd comma in the line

cmap[i,1] = row[0..c1-1]:real;

cmap[i,2] = row[c1+1..c2-1]:real;

cmap[i,3] = row[c2+1..]:real;

}

reader.close();

return cmap;

}

Here are the typical timings on a CPU:

Computing 2000x2000 Julia set ...

It took 0.382409 seconds

Plotting ...

It took 0.192508 seconds

This plotting snippet won’t work with the GPU version, as in that version the array stability is defined on

the GPU only. You can move the definition of stability to the host, and then the code with plotting on the

CPU will work. However, plotting a large heatmap can really benefit from GPU acceleration.

Question `port plotting to a GPU`

This is a take-home exercise: try porting this plotting block to a GPU. On my side, I am running into an issue assigning to a tuple element on a GPU with

colour[i,j] = ((cmap[idx,1]*255):int, (cmap[idx,2]*255):int, (cmap[idx,3]*255):int);

getting a runtime “Error calling CUDA function: an illegal memory access was encountered (Code: 700)”. Image library is still marked unstable, so perhaps this is a bug. No issues running my code on ‘CPU-as-device’.

If you succeed in running this block on a real GPU, please send me your solution.

Reduction operations

Both the prime factorization problem and the Julia set problem compute elements of a large array in parallel

on a GPU, but they don’t do any reduction (combining multiple numbers into one). It turns out, you can do

reduction operations on a GPU with the usual reduce intent in a parallel loop:

config const n = 1e8: int;

var total = 0.0;

on here.gpus[0] {

forall i in 1..n with (+ reduce total) do

total += 1.0 / i**2;

writef("total = %{###.###############}\n", total);

}

Alternatively, you can use built-in reduction operations on an array (that must reside in GPU-accessible memory), e.g.

use GPU;

config const n = 1e8: int;

on here.gpus[0] {

var a: [1..n] real;

forall i in 1..n do

a[i] = 1.0 / i**2;

writef("total = %{###.###############}\n", gpuSumReduce(a));

}

Other supported array reduction operations on GPUs are gpuMinReduce(), gpuMaxReduce(), gpuMinLocReduce()

and gpuMaxLocReduce().